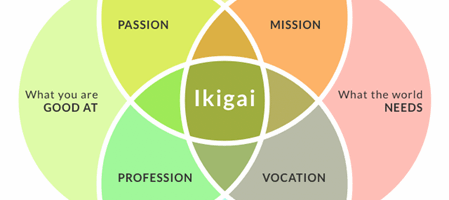

Hobbies are not your ikigai. Ikigai is a Japanese concept which, if simplified, states that the thing you can get paid for, what your good at, what the world needs and what you love should be the focus of your life.

While I love the idea of ikigai, but you need to make room for something you love doing that maybe you aren’t that good at. And that not every passion needs to be made into a side hustle.

A common complaint is that when a hobby becomes a source of income it ceases to be enjoyable. It becomes a demand instead of something you do for enjoyment. This is one of the challenges many artists face. They make art because they are creative people. If a style of art they make becomes popular, they can become stuck. Continually making that same style over and over and they stop challenging themselves. Especially if income is tied to that activity. They stop exploring and being creative, which is what brought them joy in the first place.

A great example of this is Bob Dylan. Dylan faced an immense backlash when he decided to play an electric guitar. He had become popular for his acoustic, folk music and many people didn’t want him to expand his repertoire. They wanted him to keep producing the music they liked, not the music he wanted to create. Thankfully he had the strength and means to branch out.

While Ikigai is an important concept, hobbies do not fall into this category. You are not doing it because it is what the world needs, nor because you can get paid.

Beyond Productivity: Reclaiming Joy for Its Own Sake

Perhaps the most radical aspect of maintaining true hobbies in contemporary society is their defiance of utilitarian value systems. They stand as deliberate declarations that human life encompasses more than productivity—that joy, curiosity, and personal fulfillment are themselves worthy ends. In choosing activities without obvious external rewards, we affirm our right to exist as more than economic units and reclaim portions of our time from market forces.

This perspective doesn’t diminish the importance of work, family responsibilities, or community involvement. Rather, it suggests that a life solely defined by these domains remains incomplete. The time we devote to hobbies isn’t stolen from more important priorities but properly allocated to an essential dimension of human flourishing. By modeling this balanced approach, we demonstrate to others—particularly younger generations—that worthwhile activities need not always be justified by their practical outcomes.

I believe everyone deserves these three types of hobbies not as luxuries but as necessities for psychological wellbeing and happiness. The specific activities we choose matter less than the intention behind them—the commitment to pursuing interests for their inherent joy and personal significance. In doing so, we don’t merely occupy our leisure time; we actively cultivate a richer, more textured experience of being alive.

This piece beautifully captures the essence of true hobbies—pursued for joy, not utility. It resonates deeply, reminding us to value these activities as essential for a fulfilling life beyond work and responsibilities. A must-read for anyone seeking balance.