I have broken down hobbies into three categories; physical, mental and creative. This framework, while not exhaustive, captures the fundamental dimensions of human experience in my opinion. These three domains represent the core aspects of our humanity—our embodied nature, our cognitive capacity, and our creative spirit—each requiring different forms of engagement. Each pursuit offering distinct but complementary benefits to our overall well-being.

Hobbies are so varied though that you could really break them down into as many categories as you liked. Indeed, the rich tapestry of human interests defies simple categorization. We could subdivide activities into social versus solitary pursuits, indoor versus outdoor activities, seasonal versus year-round hobbies, individual versus team-based endeavors, or traditional versus modern interests. Some might distinguish between collecting hobbies, making hobbies, performing hobbies, and exploring hobbies. Others might organize recreational activities by skill level required, time commitment needed, financial investment demanded, or physical space necessary.

Each categorization system offers its own insights into human nature and preferences. Social scientists might focus on whether activities build community connections or provide individual restoration. Psychologists might emphasize whether hobbies serve primarily for stress relief, identity formation, skill development, or meaning-making. Anthropologists might examine how recreational pursuits reflect cultural values and historical contexts. The beauty of human diversity ensures that any organizational scheme will reveal both patterns and exceptions, commonalities and unique expressions.

Some hobbies don’t really fit this model. For example, stamp collecting isn’t really mental or creative yet thousands if not millions of people enjoy it. Philately—the formal term for stamp collecting—illustrates the limitations of any rigid categorization system while simultaneously revealing the universal human drive to find meaning and pleasure in focused attention. At first glance, organizing and cataloguing stamps might seem passive or mechanical, lacking the obvious intellectual challenge of chess or the creative expression of painting.

Yet stamp collecting satisfies deep psychological needs. The activity provides a sense of order and completion in an increasingly chaotic world. Collectors experience the satisfaction of systematic organization, the thrill of discovering rare items, the pleasure of learning about history and geography through their specimens, and the meditative quality of focused, detailed attention. Many collectors develop encyclopedic knowledge about printing techniques, historical periods, geographic regions, and postal systems—demonstrating that even seemingly simple activities can engage sophisticated cognitive processes.

The social dimensions of stamp collecting further complicate easy categorization. Collectors form communities, attend conventions, engage in trades, and share expertise—transforming what might appear to be solitary activity into rich social experience. Online forums and specialized publications create networks of connection among people who might otherwise never interact. The hobby thus serves functions ranging from intellectual stimulation to social bonding to therapeutic focus, illustrating how human beings can find profound satisfaction in activities that resist simple classification.

Despite the limitations of any organizational framework, the three-part division of physical, mental, and creative pursuits captures something fundamental about human needs and flourishing. Each category addresses different aspects of our nature that require attention and cultivation for optimal wellbeing. Together, they form a balanced approach to leisure that supports holistic human development and satisfaction.

Physical Category

Humans are meant to move. Our bodies have evolved over millions of years to walk, to run, to play. The archeological record reveals our ancestors covering vast distances on foot, climbing trees and cliffs, swimming across rivers, carrying heavy loads, and engaging in complex physical activities necessary for survival. Our cardiovascular systems, musculoskeletal structures, and neurological networks all reflect this evolutionary heritage of regular, varied physical movement. The human brain itself evolved in response to the cognitive demands of navigating complex three-dimensional environments while coordinating sophisticated motor skills.

Most of us are not getting the amount of physical activity our ancestors did. The agricultural revolution began reducing daily movement requirements, but industrialization and digitization accelerated this trend dramatically. We commute in vehicles rather than walking, work at desks rather than in fields, communicate through screens rather than face-to-face interaction, and entertain ourselves through passive media consumption rather than active play. Even our household tasks require minimal physical effort thanks to modern appliances and conveniences. I even have a robot that vacuums for me!

Modern conveniences have eliminated the need for such activities and it shows in our obesity epidemic. The statistics are sobering: sedentary lifestyles contribute not only to weight gain but to increased risks of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, depression, anxiety, cognitive decline, and premature mortality. Our bodies, designed for regular movement, respond to chronic inactivity with a cascade of negative adaptations. Muscles atrophy, bones weaken, cardiovascular fitness declines, metabolic efficiency decreases, and mental acuity suffers. The very conveniences that free us from physical necessity may be undermining our physiological and psychological health.

As a result, I feel a physical hobby is imperative. Deliberate physical activity must replace the movement naturally embedded in pre-modern life. Exercise programs and gym memberships address this need partially, but they often feel like a chore and externally motivated—focused on outcomes like weight loss or muscle gain rather than inherent enjoyment. Physical hobbies offer a more sustainable and psychologically satisfying approach by combining necessary movement with genuine pleasure and personal interest.

Whether through hiking, dancing, martial arts, cycling, swimming, climbing, or countless other options, physical hobbies reintroduce our bodies to their evolutionary birthright of regular, varied movement. They provide cardiovascular benefits while engaging us in activities we actually want to do rather than feel we should do. The intrinsic motivation sustains long-term participation more effectively than exercise regimens driven by external goals or social pressure.

Mental Category

I also believe mental hobbies are also indispensable in this day and age. While our ancestors faced physical challenges that modern life has largely eliminated, we confront cognitive and emotional stressors that previous generations never experienced. The digital age subjects our brains to constant stimulation, fragmented attention, rapid decision-making demands, and overwhelming choice complexity that can exhaust our mental resources and diminish our capacity for sustained focus.

The modern world is fast paced and chaotic. We exist in a perpetual state of partial attention, shifting between email, social media, news updates, work tasks, and entertainment options without ever fully engaging with any single activity. This cognitive fragmentation may reduce our ability to experience the deep satisfaction that comes from sustained attention and skill development. The constant connectivity that defines modern life eliminates the natural boundaries between work and rest, stimulation and recovery, engagement and restoration.

Our ancestors didn’t have to deal with 24/7 news channels and social media. Their information diet consisted primarily of direct sensory experience and face-to-face communication within relatively stable communities. While they faced serious challenges—physical danger, resource scarcity, disease, and social conflict—these stressors were often concrete and time-limited rather than abstract and persistent. They enjoyed regular periods of genuine downtime when external stimulation was minimal and internal reflection was possible.

Having a hobby that helps calm the brain and center ourselves is not just a luxury but essential to maintain mental elasticity and help keep us young. Mental hobbies serve as cognitive restoration activities that allow our brains to recover from the constant demands of modern life while engaging different neural networks than those used in work and daily maintenance tasks. Activities like reading, puzzles, meditation, chess, or learning new skills provide focused attention experiences that counterbalance the scattered attention patterns dominating contemporary existence. Young people, raised on a diet of tik-tok and social media are having difficulties concentrating and focusing.

The cognitive benefits extend beyond stress relief to include improved memory, enhanced problem-solving abilities, increased mental flexibility, and potentially reduced risk of age-related cognitive decline. Mental hobbies often involve learning, which stimulates neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to form new neural connections throughout life. This ongoing cognitive challenge and growth may contribute to maintaining mental acuity and adaptability as we age.

Creative Category

Creative hobbies are necessary even for those who do not consider themselves “creative”. The misconception that creativity belongs only to a talented few—artists, writers, musicians, and other professional creators—represents one of modern culture’s most impoverishing myths. Every human being possesses creative potential. As Picasso once famously said, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up.” This quote highlights the natural creativity children possess and the difficulty many face in maintaining that artistic spirit as they age and become adults.

“Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up.” ~ Pablo Picasso

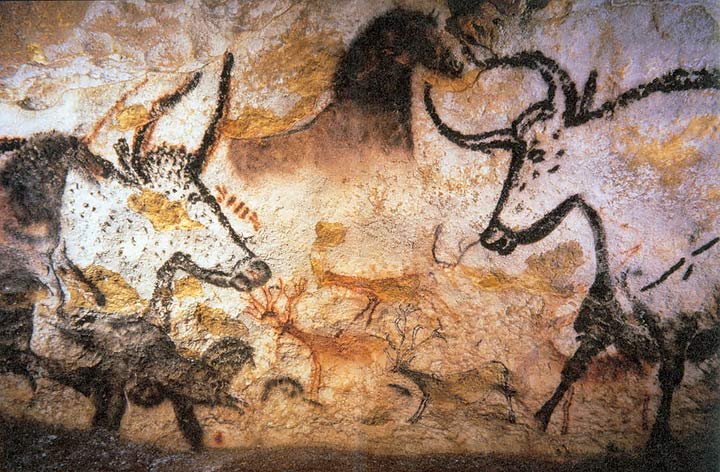

Humans have been painting and sculpting for almost as long as we’ve been on this planet. The cave paintings at Lascaux, dating back over 17,000 years, demonstrate that artistic expression emerged alongside the earliest human civilizations. These ancient works weren’t created by specialized artists but by community members who felt compelled to translate their experiences into visual form. Archaeological evidence reveals similar patterns worldwide—wherever humans settled, they created art, music, storytelling, and decorative objects that served no obvious survival function yet seemed essential to human flourishing.

Early creative expressions served multiple functions: spiritual practice, historical documentation, social bonding, individual expression, and pure aesthetic pleasure. These diverse motivations suggest that creativity meets fundamental human needs that transcend practical utility. The universality of creative expression across cultures and historical periods indicates that making, decorating, and expressing ourselves through various media represents an essential aspect of human nature rather than optional embellishment.

Creative activities help us tell our truths. Through creative expression, we access and communicate aspects of experience that resist purely rational or verbal articulation. Emotions, intuitions, spiritual insights, aesthetic perceptions, and complex relationships often require creative media to be fully expressed and understood. The process of creating—whether through visual art, music, writing, crafts, or other forms—allows us to explore and externalize internal experiences that might otherwise remain unexpressed or unexamined.

The act of creation also provides unique satisfactions: the pleasure of bringing something new into existence, the sense of agency that comes from shaping raw materials according to personal vision, the meditative absorption that creative work often induces, and the concrete evidence of one’s creative capacity. These experiences contribute to self-efficacy, personal identity, and meaning-making in ways that consumption-based activities rarely match. Ever notice how a hand-made gift gets a better reception than a store bought one?

Even for those who resist identifying as creative, engaging in creative hobbies can reveal hidden capacities and provide surprising sources of satisfaction. The person who claims they “can’t draw” might discover the meditative pleasure of pottery, even if their vessels emerge slightly lopsided. Someone who insists they lack musical ability might find joy in the rhythm and community of drumming circles. The individual convinced they’re not a writer might uncover the therapeutic benefits of journaling or the storytelling potential of photography.

The integration of physical, mental, and creative hobbies creates a balanced approach to leisure that addresses our multidimensional nature as embodied, thinking, and creating beings. While individual activities might emphasize one domain more than others, the goal is overall balance rather than perfect categorization. A life rich in varied recreational pursuits provides multiple pathways to fulfillment, resilience against life’s inevitable challenges, and ongoing opportunities for growth and discovery throughout all stages of life.

These three categories of hobbies thus represent not merely organizational conveniences but essential ingredients for human flourishing in the modern world. They address the evolutionary mismatches between our inherited nature and contemporary conditions while providing pathways to authentic engagement, personal growth, and sustainable satisfaction. In pursuing activities across these domains, we honor our complete humanity and create richer, more balanced lives that support wellbeing in all its dimensions.